Stepping into the middle of a real-life battle over voting rights

Baton Rouge native Audrey Houston Haynes, 92, reflects on an influential third grade teacher and her 'out-of-the-ordinary' lesson during Jim Crow

It was a day in the late 1930s that she’ll never forget. Audrey Houston Haynes was in the third grade at the segregated, all-Black, Scott Elementary School in East Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Her teacher, Mrs. Burnetta Franklin, took a break from the regular math lesson to teach students an unusual lesson in how to calculate their ages down to the exact number of days. “I want you to learn how to do this,” Mrs. Franklin told the class.

Audrey, 9, was confused. “This lesson was so out of the ordinary,” she said. “It was not what we were studying at the time.”

Audrey, who is now 92, did not realize that she and her third-grade classmates were stepping into the middle of a real-life battle over voting rights. It was near the end of 1939 which was the deadline to register for the upcoming 1940 presidential election. America was coming out of the Great Depression and heading into World War II. The politics of that era inspired a fresh wave of civic activism among America’s Black communities and teachers like Mrs. Franklin.

Politics and Elections

Charles Houston’s persistence to register to vote came during a historical voting shift among Black Americans who had traditionally voted Republican since the days of Abraham Lincoln and Reconstruction. In the late 1930s an increasing number of Black voters were supporting Democratic President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in his bid for a third term. As the voting registration deadline approached in 1939, a newspaper in nearby Clinton, Louisiana published an editorial under the headline “Citizens should qualify to vote.” Without directly referring to Black or White voters, the newspaper urged readers that “it is essential that the people perfect their voting qualifications.” The Watchman, Clinton, La., September 8, 1939.

Black and White Americans protested, were arrested, beaten, and murdered in the long fight for voting rights. In 1965, literacy tests were finally outlawed by the Voting Rights Act signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Voting Rights and Trick Questions

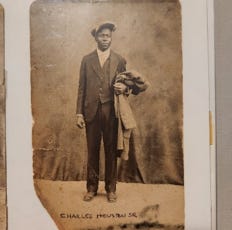

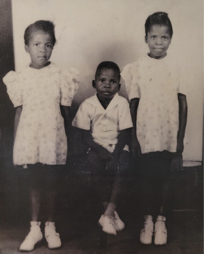

On the same day of Audrey’s unusual math lesson, her father was at the office of the registrar of voters in East Baton Rouge Parish. At age 35, Charles Houston Sr., owner of a neighborhood grocery store, was registering to vote for the first time in his life. It’s also important to note that Charles Houston Sr. was taking a big risk as a husband and father of three children. For generations, Whites had successfully used a combination of threats, intimidation, and violence to suppress the Black vote.

A key component of disfranchisement was the infamous literacy test which was much more than just a reading exam. Literacy tests consisted of various subjects and trick questions with the sole purpose of disqualifying Black people from registering to vote. For example, tax-paying, eligible citizens were required to guess how many beans were in a jar. Another trick question: Spell backwards forwards. The answers were graded subjectively. White clerks in Louisiana and across the Deep South had the law on their side to reject any answer and test taker based solely on skin color.

At home that evening, Houston shared disappointing news with his family. He was unable to register to vote because he missed a question on the literacy test. On top of that, when he vowed to return and retake the test, the clerk threatened him, “If you come back here tomorrow, you’re going to jail,” Haynes remembered.

This was a common experience for Black people especially in the South. But then, Houston revealed exactly which test question he missed. To her surprise, he missed a trick question about calculating his age down to the day.

“Oh, we know how to do that!” exclaimed the young Audrey, referring to Mrs. Franklin’s lesson earlier that day.

Haynes said she remembers sitting down at the kitchen table with her father that evening. Together they reviewed the lesson on calculating your age down to the day. The next morning, Houston ignored the jail threat and returned to the clerk’s office. He passed the test and registered to vote.

It all made sense to Audrey Houston Haynes years later, when she realized that Mrs. Franklin was working behind-the-scenes to prepare Black children with lessons that would help their parents pass the literacy test.

Reflections of a Lifelong Educator

A 1952 graduate of Southern University, Audrey Houston Haynes enjoyed a long career as an educator in public schools in Louisiana and eventually Portland, Oregon where she and her husband raised two children. She served as a high school principal before retiring in 1992.

At 92, she reflects on the challenges her family faced in the fight for voting rights. Her teacher, Mrs. Franklin, risked job security to work “undercover” to ensure Black families were prepared for trick questions on the literacy test. Even though she taught at an all-Black public school, Mrs. Franklin was employed by an all-White administration. “Mrs. Franklin could not tell us why she was teaching us that lesson because she could have lost her job,” said Haynes.

Following her father’s successful voter registration, she said her mother, Sara Albertha Houston, a beautician, also registered for the first time. The discrimination Haynes witnessed first-hand as a child is a big reason why she refuses to take voting rights for granted. She thanks Mrs. Franklin for that important lesson. “She was a brave soldier for freedom,” said Haynes.

By Carlton Houston

Carlton Houston is a former journalist, historian, and nephew of Audrey Houston Haynes. You can learn more about his family history on Instagram @myhistoryvibe.

In all-black schools, there is a lesson that we all learn.